Ancient Ships: The Ships of Antiquity

Ancient Ships in art history: Illustrations from Greek Pottery

of the History of Ancient Greece, the Greek Epic Poems and the Trojan

War

Illustrations of Themes from Classical Greek Literature

It is fortunate for sake of Greek history that verbal descriptions

of Bronze Age ships from ancient Greece abound in the stories of

Homer. However the identity of Homer is not entirely certain and

the stories which make up the Iliad and the Odyssey may be

the products of a long oral tradition of story telling in the ancient

Greek culture which were not committed to written text until as

late as the 6th Century BCE, however it is Homer who is criedited

to have committed these stories to their first written copies. Under

such circumstances  errors

and anachronisms might be expected to abound in accounts of events

that took place during the Trojan war as much as 600 years earlier.

For the practical historian it is noteworthy that in practice the

ships described in Homer appear to be carefully delineated from

those of the period in which the texts were actually written. For

example Homer never speaks of a ship of the Trojan war using a ram,

although the ram was a prominent feature of post 8th century BCE

Greek galleys, nor does he describe multi-banked galleys, which

are found in Greek ship iconography after the 8th century

BCE and before the Homeric poems were written. We can assume that

Homer was familiar with these elements of ship technology but did

not mention these features as part of the configuration of the ships

that were used during the Trojan Wars and its' period of Greek history. errors

and anachronisms might be expected to abound in accounts of events

that took place during the Trojan war as much as 600 years earlier.

For the practical historian it is noteworthy that in practice the

ships described in Homer appear to be carefully delineated from

those of the period in which the texts were actually written. For

example Homer never speaks of a ship of the Trojan war using a ram,

although the ram was a prominent feature of post 8th century BCE

Greek galleys, nor does he describe multi-banked galleys, which

are found in Greek ship iconography after the 8th century

BCE and before the Homeric poems were written. We can assume that

Homer was familiar with these elements of ship technology but did

not mention these features as part of the configuration of the ships

that were used during the Trojan Wars and its' period of Greek history.

Ship image from a late Geometric Krater circa 760-750 BC restored

in Photoshop

The

true advantage that we have is that the artisans of the ancient

Greek culture often illustrated events similar to those that

are described in the stories written by the Greek poets. Similar

themes to those in the classical Greek Poems were frequently

painted on Vases and other ceramics starting as early as the Geometric

period 1600 BCE. The

true advantage that we have is that the artisans of the ancient

Greek culture often illustrated events similar to those that

are described in the stories written by the Greek poets. Similar

themes to those in the classical Greek Poems were frequently

painted on Vases and other ceramics starting as early as the Geometric

period 1600 BCE.

Later illustrations on Attic vases reflected classical

Greek Literary and mythological themes. Attic vases were containers

and can be thought of in many respects to be the first commercial

packaging with pictures on them. The artisans would take a utilitarian

item and decorate them with aspects of story lines from Greek culture.

For simple artistic reasonís few utilitarian items are richer in

their content than the Greek attic vases.

This decorative tradition was begun in the area

of Aegean Sea with the Minoan potters as early as 1700BCE.

It should be noted that the iconography of daily life was painted

on pottery and recorded as decorum in the culture long before

written records of the same activities began to occur as classical

Greek literature and poetry. This trend of the artisans illustrating

aspects of the Greek culture in which they lived in non textual

Iconographies prior to the introduction of formal writing systems

is true for cultures other that the Agean as well as the early Agean

Cultures. These illustrations within their archeoloical context

give archeologists and investigators the advantage of being able

to see and understand aspects of the culture of ancient Greece which

are not clearly delineated in the written records of

the Greek culture.

Someone in their wisdom has said a picture is worth

a thousand words. In the case of the prehistoric cultures of the

Aegean Sea we often have a visual record that tells a story, all

you have to do is read the writing on the wall or pottery so to

speak, in order to see various aspects of the story of these prehistoric

Agean cultures.

The ships found in Homer are usually described as fast and hollow,

which means without a deck or open, long, narrow, low and light,

with black painted hulls. There were no accommodations for living

in them and they were built to be hauled onto a beach at night so

that the crews could camp on the shore. Speed and flexibility were

the premium with these boats. Gear was stowed under vestigial decks

at the stem and the stern. These are also features that were also

common to later Greek warships, most notably the trieres or trireme.

The key to the speed of and ability to navigate these

ships were the crews. Men on oars were the mechanism for maneuverability

and the wind in their sails was the primary motor for long

distance travel.

Phoenician

Coin Phoenician

Coin

Homer classifies his ships into a number of well-defined types

that have no exact parallel in the ships of the 8th century. There

are, for example, small twenty oared galleys used for transport,

exploration or dispatch duties. The fifty oared pentecontor (25

oars per side) which was used as a troop carrier, and the larger

100 oared vessels (50) per side) which were used as heavy transports.

He does not anywhere in his writing mention the thirty-oared

triacontor, which was in common use in the eight century BC.

A Greek war ship from the time of the Persian wars Circa 600 BCE

Amphora

Pottery of the Cyclidic culture from Thera 1600 BCE demonstrates

the extensive use of iconography for decorative purposes within

the Aegean Cultures. These types of features were traditionally

used on pottery of the Aegean cultures, though they varied

in style and proficiency of execution, for the next 1400 years.

The images in this iconography gives us clues to cultural exchanges

that occurred which would be unavailable through the written

records. Much of the Iconography suggests several cultural

influences and where written records are not available are

the only means to do analysis of the social dynamics of the ancient

world.

Where

shipbuilding is discussed in Homer, most obviously in the famous

passage from Calypso's island, Homer speaks in technological terms

such as keels, stem and sternposts, frames, planks, gunwales,

cross beams and through beams fastened with treenails and mortise

and tendon joints fabricated from a variety of preferred woods

including oak, poplar, pine and fir. These methods of construction

were certainly common in the eight century and had probably developed

from similar methods used in the previous millennium. One of the

best records of ship iconography from this historic era are those

recorded by the Egyptians during the Invasion of the Sea peoples

into Egypt during approximately the same time period of 1200 BCE. Where

shipbuilding is discussed in Homer, most obviously in the famous

passage from Calypso's island, Homer speaks in technological terms

such as keels, stem and sternposts, frames, planks, gunwales,

cross beams and through beams fastened with treenails and mortise

and tendon joints fabricated from a variety of preferred woods

including oak, poplar, pine and fir. These methods of construction

were certainly common in the eight century and had probably developed

from similar methods used in the previous millennium. One of the

best records of ship iconography from this historic era are those

recorded by the Egyptians during the Invasion of the Sea peoples

into Egypt during approximately the same time period of 1200 BCE.

An overview of iconography from the eastern

Mediterranean would suggest that the ship building technologies

were know and shared between cultures. The Egyptians were

known to have sought the support of ship builders and traded

for timbers for ship building from Byblos as early as the construction

of the Pyramid complex of the Pharaoh Sahure 2450 BCE.

This would explain the projecting forefoot,

not at this stage a ram, which is characteristic of the limited

iconography for this period, particularly the Pylos vase and the

Gazi Larnax as having derived from Egyptian ships which prominently

featured these characteristics as early as 1250 BCE.

Illustration of Ships form the time of the Iliad, see

similar images on Greek attic pottery at the Perseus

Project

The

oars in Homeric galleys were rowed against thole pins and held in

place by a leather strap. Only one steering oar was used , again

this is consistent with the twelfth century Mycenaean iconography,

and also with the ships illustrated in Thera Frescos from the 16

th Century BCE. Twin steering oars were standard by the 6th

century. Where sails are described the mast was usually dismountable

and was set in the tabernacle above the keel and held in place by

two forestays and one backstay without shrouds. A single loose-footed

square sail was used made up of patches of linen. Standing rigging

included braces to the yardarm, sheets, and brailing lines. Homeric

ships were also expected to carry lines and stone anchors, and they

may have been equipped with bilge drain plugs to facilitate and

drying out the boats after beaching. The

oars in Homeric galleys were rowed against thole pins and held in

place by a leather strap. Only one steering oar was used , again

this is consistent with the twelfth century Mycenaean iconography,

and also with the ships illustrated in Thera Frescos from the 16

th Century BCE. Twin steering oars were standard by the 6th

century. Where sails are described the mast was usually dismountable

and was set in the tabernacle above the keel and held in place by

two forestays and one backstay without shrouds. A single loose-footed

square sail was used made up of patches of linen. Standing rigging

included braces to the yardarm, sheets, and brailing lines. Homeric

ships were also expected to carry lines and stone anchors, and they

may have been equipped with bilge drain plugs to facilitate and

drying out the boats after beaching.

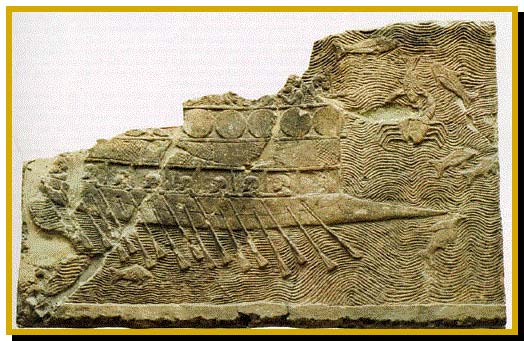

Phoenician Ship From 800 BCE Stone Relief Sculpture

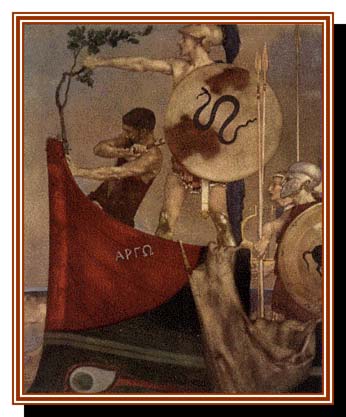

The Argo

Argo was the name of a Greek navigation system.

The

Argo was built near Pelion Mount most possibly at Pagasses. The

story of the Argos is pure high adventure. The men who took

part in the expedition were called Argonautae or Minyas, and the

journey was the Argonautica Expedition or the Argonautica. The

Argo was built near Pelion Mount most possibly at Pagasses. The

story of the Argos is pure high adventure. The men who took

part in the expedition were called Argonautae or Minyas, and the

journey was the Argonautica Expedition or the Argonautica.

The shape of the ship was oblong and this is the

reason for giving her the name "the long vessel", as well.

It was the first long vessel as, until that time, the Greeks

had been using mostly small round-shaped ships. Some sources

say that the Argo was a fifty-oared ship while some others say that

there were thirty oars on each side. Hence, they estimate that the

Argo's length must have been between 22 or 25 meters. The wood that

was used was probably oak and pine. The Argo was equipped with all

those implements and tacking necessary for the management and guiding

of the ship. It was a hard constructed ship, able to sail in open

seas and stand up well to the blows of huge waves.

Although

the Argo - and most prehistoric Hellenic ships - had no engine,

she had a great advantage compared to the ships of today. The ship

would not need a port to call at. Because of her low draught she

could be hauled ashore at the convenience of the crew as weather

or other circumstances may have demanded. Although

the Argo - and most prehistoric Hellenic ships - had no engine,

she had a great advantage compared to the ships of today. The ship

would not need a port to call at. Because of her low draught she

could be hauled ashore at the convenience of the crew as weather

or other circumstances may have demanded.

Because she had to be hauled up the beach in order

to avoid possible destruction by a sea-storm, the Argo did not have

a deck as its additional weight would render her hauling more difficult

or impossible. The ability to haul ashore was a great advantage

of the prehistoric Hellenic vessels, which made possible the accomplishment

of those amazing and incredible explorations made at that time.

At the prow of the ship Athena fitted in a "speaking"

timber from the oak of Dodona, which would advise the Argonauts

on the right course. In fact, that "speaking " timber

("Koraki" in the Hellenic nautical terminology) operated

like a compass, and it corresponded to the North while the steering

oar ("Diaki" in the Hellenic nautical terminology) to

the South. The imaginary line between the steering oar and the "speaking"

timber extended towards a certain point of the horizon-which was

determined by the positions of stars (I.E. the Pole Star)- enabled

the Captain to trace the course of the ship approximately

Fortunately for the person interested in this period

of Greek history even quite small boats represent a considerable

expenditure of labor and wealth and required a high degree of organization

to navigate and operate. Boats  therefore were usually valuable and prized objects in the societies

that produced them. Boats are also relatively large structures.

Indeed they are still probably the largest moving objects made by

man and for this reason alone ships and boats have imposed

themselves on the imaginations of artists and story tellers from

the earliest times to the present day. We are fortunate to have

pictures of ships appear in many forms and in many different places.

therefore were usually valuable and prized objects in the societies

that produced them. Boats are also relatively large structures.

Indeed they are still probably the largest moving objects made by

man and for this reason alone ships and boats have imposed

themselves on the imaginations of artists and story tellers from

the earliest times to the present day. We are fortunate to have

pictures of ships appear in many forms and in many different places.

The formulation of crews to man the ships represented

a major commitment and effort to create team work, all involved

knowing they were dependent on one another for the ultimate success

of the voyages.

Where societies were particularly reliant on ships

for trade and war the ship became an important part of the culture,

perhaps a dominant part as in the case of the Egyptians, Phoenicians,

Greeks and the Vikings. Traditionally and by definition the seafaring

boat and ship has been identified with trading enterprises and exploratory

adventures into the unknown and in some cultures it was associated

with the ultimate voyage from life to death, which is why boats

find their way into Egyptian pyramids and the graves of Saxon and

Viking nobles. From antiquity to the Renaissance the ship became

the vehicle for exploration and discovery into Africa and the Known

World. In this role, too, ships and boats have appealed to the artist

and cultural historian.

Fortunately representations of ships are widespread

throughout recorded history. How accurate these pictures are is

another matter, depending on the cultural attitudes and technical

competence of the artists. Ship iconography as found on artifacts

is beset with distortions however the images remain from antiquity

giving us critical and credible clues to the use and evolution of

ships and boats in various cultures.

Fortunately modern archeology is allowing us to

fill in some of the blanks as deep water finds are revealing additional

information on ship building technologies and trade associations.

A Greek crew setting ashore

Compare this image to the Original

on a Greek vase dated 540BCE

Greek history

An

outlined study of Greek Colonization in the Mediterranean

from the time of the Trojan Wars 1200 BCE

to The time of Alexander the Great 300 BCE

Previous |

Next | Table Of Contents

|