"At the period of which I write, in (winter)

1868, the Plains were covered with vast herds of buffalo—the

number has been estimated at 3,000,000 head—and with such

means of subsistence as this everywhere at hand, the 6,000 hostiles

were wholly unhampered by any problem of food-supply. The savages

were rich too according to Indian standards, many a lodge owning

from twenty to a hundred ponies; and consciousness of wealth and

power, aided by former temporizing, had made them not only confident

but defiant."

Quote from PERSONAL MEMOIRS OF PHILIP. H. SHERIDAN

VOLUME II. Part 6 CHAPTER XII

"These men (the buffalo hunters) have done more

to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army

has done in the last thirty years. They are destroying the Indians'

commissary. Send them powder and lead if you will, but for the sake

of a lasting peace let them kill, skin and sell until the buffalo

are extermininated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled

cattle and the festive cowboy who follows the hunter as the second

forerunner of an advanced civilization."--General Philip H.

Sheridan

William Cody while in the Kansas territory and

upon meeting a group of military men preparing for a buffalo hunt

in the summer of 1868. He gave the following account of how he won

his name.

Source: LAST OF THE GREAT SCOUTS (BUFFALO BILL)

BY HELEN CODY WETMORE AND ZANE GREY

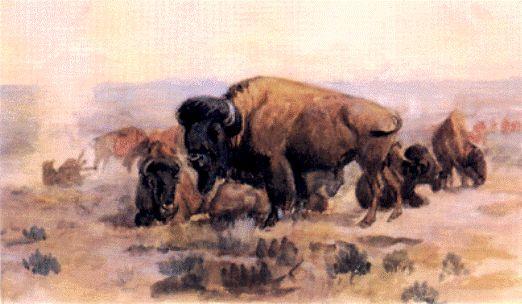

American Bison by Chester Comstock

American Bison by Chester Comstock

commissioned to honor donors to

"The Villages" Florida charter school

© 2007 Comstock Sculpture Studio

"Come along with us," offered the captain

graciously. "We’re going to kill a few buffalo for

sport, and all we care for are the tongues and a chunk of the

tenderloin; you can have the rest.

"Thank you," said Will. "I’ll

follow along."

Nearby there were eleven buffaloes in the herd,

and the officers started after them as if they had a sure thing

on the entire number. Will noticed that the game was pointed toward

a creek, and understanding "the nature of the beast,"

started for the water, to head them off.

As the herd went past him, with the military

quintet five hundred yards in the rear, he gave Brigham’s

blind bridle a twitch, and in a few jumps the trained hunter was

at the side of the rear buffalo; Lucretia Borgia spoke, and the

buffalo fell dead. Without even a bridle signal, Brigham was promptly

at the side of the next buffalo, not ten feet away, and this,

too, fell at the first shot. The maneuver was repeated until the

last buffalo went down. Twelve shots had been fired; then Brigham,

who never wasted his strength, stopped. The officers had not had

even a shot at the game. Astonishment was written on their faces

as they rode up.

"Gentlemen," said Will, courteously,

as he dismounted, "allow me to present you with eleven tongues

and as much of the tenderloin as you wish."

"By Jove!" exclaimed the captain, "I

never saw anything like that before. Who are you, anyway?"

"Bill Cody’s my name."

"Well, Bill Cody, you know how to kill buffalo,

and that horse of yours has some good running points, after all."

"One or two," smiled Will.

Captain Graham—as his name proved to be

— and his companions were a trifle sore over missing even

the opportunity of a shot, but they professed to be more than

repaid for their disappointment by witnessing a feat they had

not supposed possible in a white man—hunting buffalo without

a saddle, bridle, or reins. Will explained that Brigham knew more

about the business than most two-legged hunters. All the rider

was expected to do was to shoot the buffalo. If the first shot

failed, Brigham allowed another; if this, too, failed Brigham

lost patience, and was as likely as not to drop the matter then

and there.

It was this episode that fastened the name of

"Buffalo Bill" upon Will, and learning of it, the friends

of Billy Comstock, chief of scouts at Fort Wallace, filed a protest.

Comstock, they said, was Cody’s superior as a buffalo-hunter.

So a match was arranged to determine whether it should be "Buffalo

Bill’ Cody or "Buffalo Bill" Comstock.

Charlie Russell's painting of a Bull Buffalo

Charlie Russell's painting of a Bull Buffalo

The hunting-ground was fixed near Sheridan, Kansas,

and quite a crowd of spectators was attracted by the news of the

contest. Officers, soldiers, plainsmen, and railroad men took

a day off to see the sport, and one excursion party, including

many ladies, among them Louise, came up from St. Louis.

Referees were appointed to follow each man and

keep a tally of the buffaloes slain. Comstock was mounted on his

favorite horse, and carried a Henry rifle of large calibre. Brigham

and Lucretia went with Will. The two hunters rode side by side

until the first herd was sighted and the word given, when off

they dashed to the attack, separating to the right and left. In

this first trial Will killed thirty-eight and Comstock twenty-three.

They had ridden miles, and the carcasses of the dead buffaloes

were strung all over the prairie. Luncheon was served at noon,

and scarcely was it over when another herd was sighted, composed

mainly of cows with their calves. The damage to this herd was

eighteen and fourteen, in favor of Cody.

In those days the prairies were alive with buffaloes,

and a third herd put in an appearance before the rifle-barrels

were cooled. In order to give Brigham a share of the glory, Will

pulled off saddle and bridle, and advanced bareback to the slaughter.

That closed the contest. Score, sixty-nine to

forty-eight. Comstock’s friends surrendered, and Cody was

dubbed "Champion Buffalo Hunter of the Plains."

The heads of the buffaloes that fell in this

hunt were mounted by the Kansas Pacific Railroad Company, and

distributed about the country, as advertisements of the region

the new road was traversing. Meanwhile, Will continued hunting

for the Kansas Pacific contractors, and during the year and a

half that he supplied them with fresh meat he killed four thousand

two hundred and eighty buffaloes. But when the railroad reached

Sheridan it was decided to build no farther at that time, and

Will was obliged to look for other work.

End of story from: LAST OF THE GREAT SCOUTS (BUFFALO

BILL)

Comstock's story ended a few months after his

contest with Bill Cody. During the summer and into the fall of

1868 indians were on the rampage in the Kansas territory. As to

the nature of their activities and Comstock's death see the follow

excerpt from Gen, Philip Sheridan's Memoirs.

"Leaving the Saline, this war-party crossed

over to the valley of the Solomon, a more thickly settled region,

and where the people were in better circumstances, their farms

having been started two or three years before. Unaware of the

hostile character of the raiders, the people here received them

in the friendliest way, providing food, and even giving them ammunition,

little dreaming of what was impending. These kindnesses were requited

with murder and pillage, and worse, for all the women who fell

into their hands were subjected to horrors indescribable by words.

Here also the first murders were committed, thirteen men and two

women being killed. Then, after burning five houses and stealing

all the horses they could find, they turned back toward the Saline,

carrying away as prisoners two little girls named Bell, who have

never been heard of since."

When this frightful raid was taking place, Lieutenant

Beecher, with his three scouts—Comstock, Grover, and Parr—was

on Walnut Creek. Indefinite rumors about troubles on the Saline

and Solomon reaching him, he immediately sent Comstock and Grover

over to the headwaters of the Solomon, to the camp of a band of

Cheyennes, whose chief was called "Turkey Leg," to see

if any of the raiders belonged there; to learn the facts, and

make explanations, if it was found that the white people had been

at fault. For years this chief had been a special friend of Comstock

and Grover. They had trapped, hunted, and lived with his band,

and from this intimacy they felt confident of being able to get

"Turkey Leg" to quiet his people, if any of them were

engaged in the raid; and, at all events, they expected, through

him and his band, to influence the rest of the Cheyennes. From

the moment they arrived in the Indian village, however, the two

scouts met with a very cold reception. Neither friendly pipe nor

food was offered them, and before they could recover from their

chilling reception, they were peremptorily ordered out of the

village, with the intimation that when the Cheyennes were on the

war-path the presence of whites was intolerable. The scouts were

prompt to leave, of course, and for a few miles were accompanied

by an escort of seven young men, who said they were sent with

them to protect the two from harm. As the party rode along over

the prairie, such a depth of attachment was professed for Comstock

and Grover that, notwithstanding all the experience of their past

lives, they were thoroughly deceived, and in the midst of a friendly

conversation some of the young warriors fell suddenly to the rear

and treacherously fired on them.

At the volley Comstock fell from his horse instantly

killed. Grover, badly wounded in the shoulder, also fell to the

ground near Comstock Seeing his comrade was dead, Grover made

use of his friend's body to protect himself, lying close behind

it. Then took place a remarkable contest, Grover, alone and severely

wounded, obstinately fighting the seven Indians, and holding them

at bay for the rest of the day. Being an expert shot, and having

a long-range repeating rifle, he "stood off" the savages

till dark. Then cautiously crawling away on his belly to a deep

ravine, he lay close, suffering terribly from his wound, till

the following night, when, setting out for Fort Wallace, he arrived

there the succeeding day, almost crazed from pain and exhaustion.

PERSONAL MEMOIRS OF P. H. SHERIDAN VOLUME II. Part

6 CHAPTER XII.

Publisher: Charles L. Webster & Company 1888

William Comstock met his death on August 27,

1868, in his twenty-sixth year.

Due to the hostilities being conducted by the

indians Sheridan prepared his command to conduct a winter campaign

against the raiders. The plight of the indians and the future

of free ranging hunting parties in pursuit of buffalo essentially

had come to end. The Medicine Lodge treaty of Oct. 1867 stipulated

that the indians would retire to designated reservations and that

Indians roaming outside of the reservations were in violation

of the treaty.

Gen. Philip Sheridan submitted the following

report to General Sherman dated November 1, 1869 describing the

military operations in the Department of the Missouri from October

15, 1868 through March 27, 1869. The report included a sworn statement

from Edmund "Guerriere" which was titled "In

the field, Medicine Bluff Creek, Wichita Mountains, February 9th,

1869." Guerrier's statement was this:

"I was with Cheyenne Indians at the time

of the massacre on the Solomon and Saline rivers in Kansas, the

early part or middle of last August, and I was living at this

time with Little Rock's band. The war party who started for the

Solomon and Saline was Little Rock's, Black Kettle's, Medicine

Arrow's and Bull Bear's bands; and as near as I can remember,

nearly all the different bands of Cheyennes had some of their

young men in this war party which committed the out rages and

murders on the Solomon and Saline. Red Nose, and The-man-who-breaks-the-marrow

bones, [Ho-eh-a-mo-a-hoe] were the two leaders in this massacre;

the former belonged to the Dog Soldiers, and the latter in Black

Kettle's band. As soon as we heard the news by runners who came

on ahead to Black Kettle - saying that they had already commenced

fighting, we moved from our camp on Buckner's Fork of the Pawnee,

near the head waters, down to North Fork, where we met Big Jake's

band, and then moved south, across the Arkansas river; and when

we got to the Cimarron, George Bent and I left them and went to

our homes on the Purgatoire."

Sheridan seems to use this statement, in part,

as justification for Custer's attack on Black Kettle's encampment

at Washita.

The year 1867 with the signing of the Medicine

Bow Treaty marks the end of the old west and the beginning of

the wild west.

During his command of the Department

of the Missouri Sheridan sought out and hired the best men

he could find to be guides for his military units. Among the

men he hired for this position were William Cody and William

Comstock and Wild Bill Hickock. All three if these men had

been ponie express riders during its brief history.

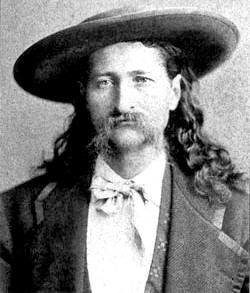

Wild Bill Hickock was a friend and

companion of Buffalo Bill Cody as a buffalo hunter in the

Kansas Territory

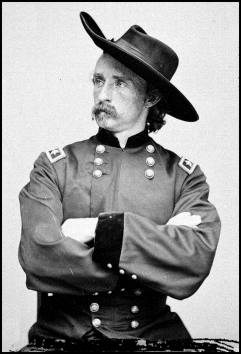

George Armstong Custer

was one of Sheridans favorite subordinates during his

Missouri Command

"On the first of June1867 , with about three

hundred and fifty men and a train of twenty wagons, I left Fort

Hays and directed our line of march toward Fort McPherson, on

the Platte River, distant by the proposed route two hundred

and twenty-five miles. The friendly Delawares accompanied us

as scouts and trailers, but our guide was a young white man

known on the Plains as Will Comstock. No Indian knew the country

more thoroughly than did Comstock. He was perfectly familiar

with every divide, water-course, and strip of timber for hundreds

of miles in either direction. He knew the dress and peculiarities

of every Indian tribe, and spoke the languages of many of them.

Perfect in horsemanship, fearless in manner, a splendid hunter,

and a gentleman by instinct, as modest and unassuming as he

was brave, he was an interesting as well as valuable companion

on a march such as was then before us. Many were the adventures

and incidents of frontier life with which he was accustomed

to entertain us when around the camp-fire or on the march. Little

did he then imagine that his own life would soon be given as

a sacrifice to his daring, and that he, with all his experience

among the savages, would fall a victim of Indian treachery."

Quoted from the Memoirs of Gen. George Armstrong

Custer

Standard Issue of Cavalry soldier's

riding gear during the Indian Wars. Image has a link to

articles about Sheridans Buffalo Soldiers the 9th and 10th

Cavalry

Articles on the expansion

of the American west and the fate of the American Buffalo

during the American 19th century

|